In celebration of Polimoda’s recent acquisition of Rick Owens pieces for AN/ARCHIVE, we present this illuminating article by fashion historian and faculty member Aurora Fiorentini, first published on occasion of the designer’s groundbreaking 2018 exhibition at the Triennale di Milano.

The article highlights how Owens’ distinctive vision merges diverse artistic elements through paradoxical combinations, revealing a distinctive fashion philosophy and a complex aesthetic vocabulary that draws inspiration from ancient rituals, primordial forces and artistic movements, all contributing to an oeuvre which challenges conventional fashion norms.

The Rick Owens solo show, held from December to March 2018 at the Triennale di Milano, triggered powerful points of reflection in both the aesthetic and conceptual realms of fashion. Here, the word acquired a new meaning, becoming the glue binding diverse contemporary artistic languages – from sculpture to photography, design and music – into a single homogenous current.

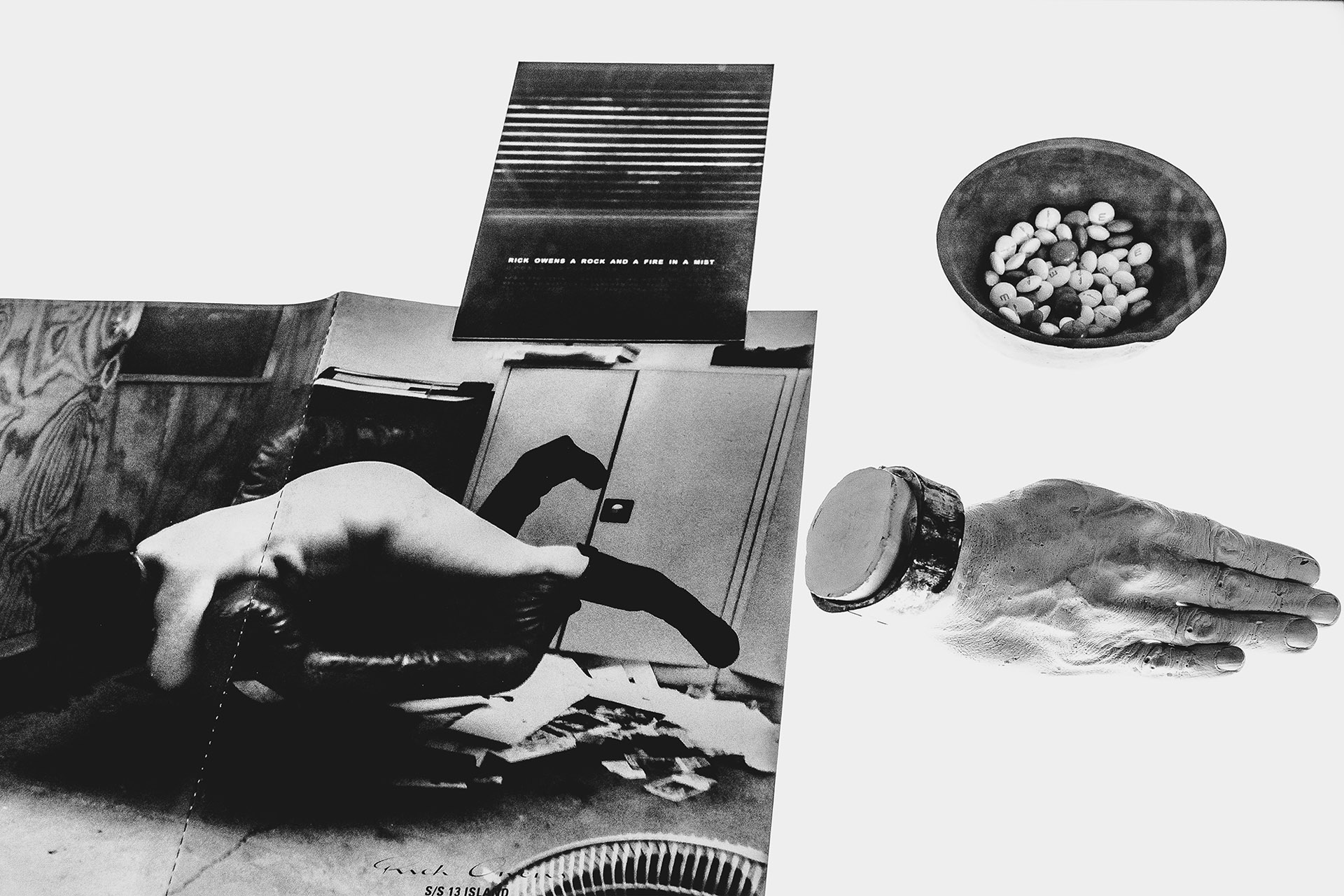

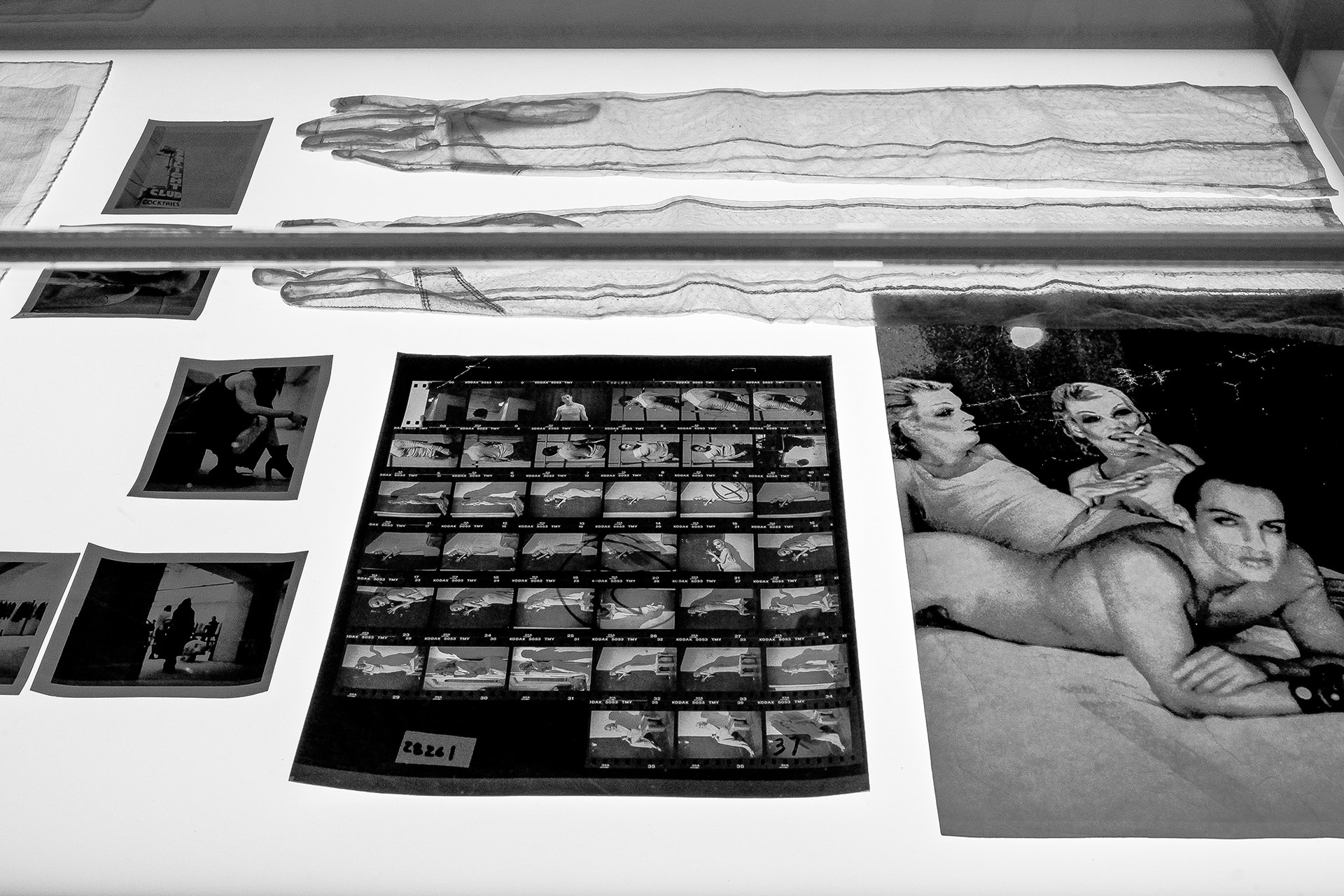

The exhibit – a selection of more than one hundred garments, symbolic objects, accessories, graphics, furniture and fashion show videos selected by Owens himself – became a moment to delve into the linguistic semantics of the California creative’s collections from incipit to today. And in the complexity of the themes and styles dealt with, it employed an array of unusual lenses through which one of the most influential visionaries of our time was ultimately revealed.

Rick Owens remains among the most radical and discussed figures of contemporary fashion. His work is persistent, innovative, iconoclastic and unpredictable, all translated and rendered tangible through shapes, volumes and contemporary materials saturated with primal echoes, deliberately misaligned and deconstructed: “I am hesitant to define what I do as art. I think in three dimensions, so this has a lot to do with the construction, and less with the styling, let’s say it’s much more similar to sculpture, but I do not want to call it art … ” (Rick Owens e la moda dell’Io Profondo, 2017).

With these words, the introverted designer seems to taunt, clearly defining his particular approach to design. His work desires above all to escape the excessive clamor of the mainstream with a refined yet complex aesthetic message, deliberately both critical and free of banal commercial logistics of conventional fashion. Here, goth and grunge elements act as a connective tissue of an unequivocal aesthetic grid.

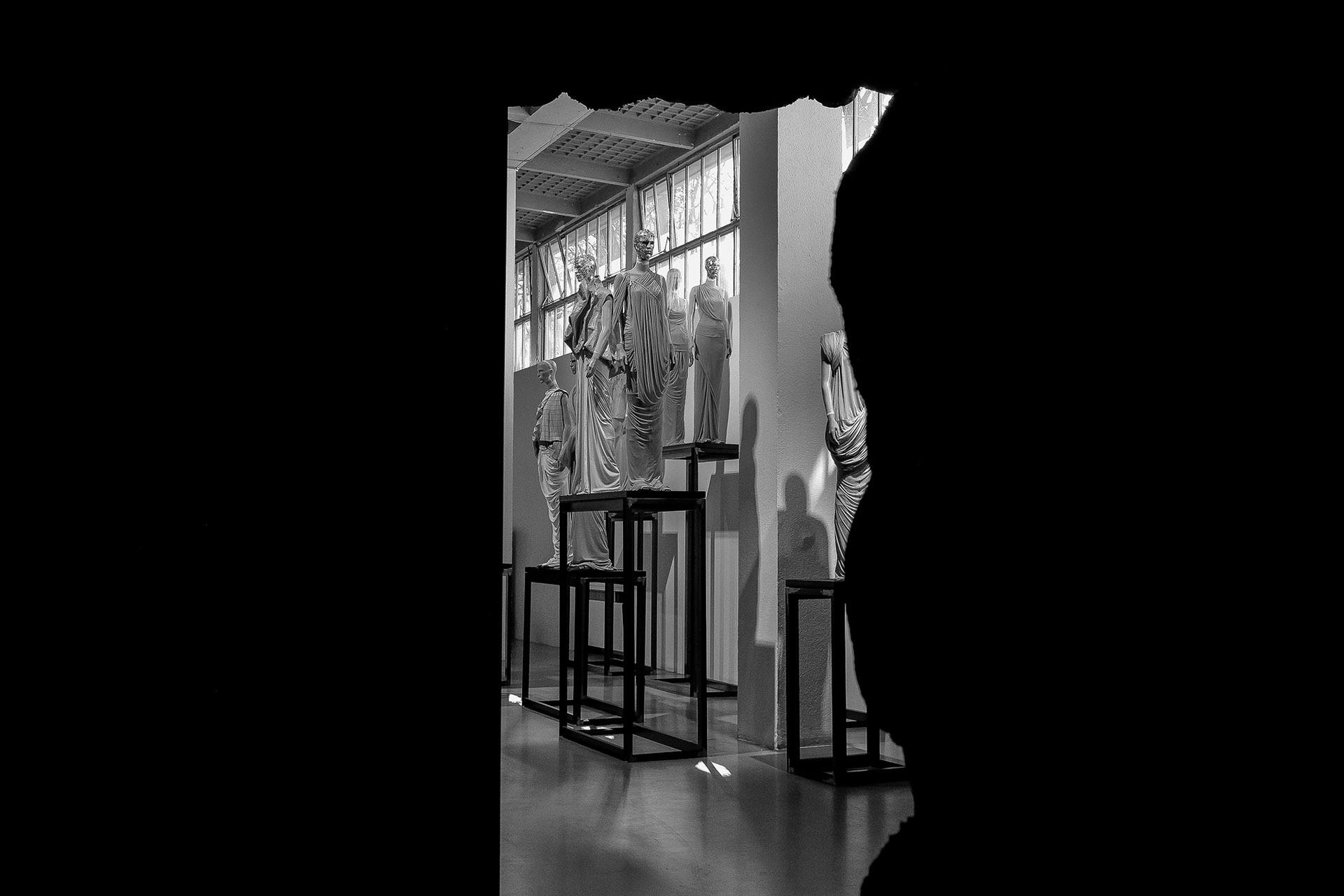

And at the heart of the Triennale exhibit, a three-dimensional, colossal, material on-site installation became a giant essence meant to continuously underline these glam, grunge and radical elements of its creator – a figure for whom the term “glunge” was specifically coined.

The massive, snaking installation, clot-like in form, underlined the profound paradoxes that have always distinguished the designer. Antithetical concepts such as order and chaos, light and darkness, natural and artificial, construction and deconstruction, are exalted via this sculptural element defined by Owens as the “primal howl” or “ectoplasmic vomit” (Numero 191, 2018), which, like a sort of alchemical mixture, is composed of cement, sand from the Adriatic, lily powder and his hair.

This alien form interrupted the perfect symmetry of the 1930s building designed by Giovanni Muzio, one of the chief expressions of Italian rationalist architecture characterized by clean lines and balance of volumes. The “clot” became the dissonant element bringing back algid perfection to the disorder, which dirtied and reified the surrounding space, making it simultaneously more human and contaminated.

For Owens, references to conceptual Land Art artists such as Richard Serra, and more so Richard Long and Michael Heizer, are essential. They fully grasp its poetic and symbolic anthropology, something capable of conveying a sense of primordiality and eternity, which immediately contrasted the fragile and fluid immanence of the clothes on display.

Decadent and almost funereal, attracted to the exhausting aestheticism of Gustave Moreau and Joris-Karl Huysmans – whose copy of À rebours he has on his nightstand – Owens is interested in many aspects of contemporary art and literature. From Le Corbusier’s architectural brutalism to Alison Gill and Carlo Scarpa’s research on the weight of anti-decorative structural elements (such as concrete and steel), as well as Brâncusi, Beuys, Fontana, Kiefer, Schnabel, the irreverent provocations of arte povera, Piero Manzoni’s monochromes (Merda d’artista, 1961 and Achrome, 1957-1963) and the installations of Steven Parrino (13 Shattered Panels for Joey Ramone, 2001). These figures have all questioned the canonical concepts of beauty accepted in painting and sculpture, which the American designer analogously has underlined in his fashion.

But the looming snake installation is first and foremost a metaphor for Rick Owens’ creative process: “Contrast is always in my inspirations. The indecision between collapse and control, brutality and refinement, grace and ugliness” (East touch magazine, 2002).

And within this immaterial struggle of archetypal forces lies the appeal of Owens’ style and the imperfect beauty of his creations.

The result is an immersion in his universe, the sum of a process of imploding conformism, common beliefs and decency, which favors creativity as pushed to counteract false moralism through overlapping designs and surprising connections. The clothes selected in the Triennale were not presented in chronological order, an obvious approach, but were juxtaposed in such a way where the past and the future, perceived through the present, merged into a deliberately a-historical dimension, inhabited by mannequins that possessed both an earthly and alien humanity.

Owens’ fascination with ancient rituals and primordial forces has resulted in a sartorial design that deconstructs denim, leather, knit, felt and canvas, linking the designer’s first works – made with military uniforms and bags from Vietnam – to his most recent woolen knits, silk drapes, cashmere and jersey, all wrapped and thrown off balance both on and beyond the body.

At the same time, each section of the exhibition was measured through the grouping of iconic garments by color, especially black, gray, ivory, Nile green or mud. The non-colored colors – rare, precious and simultaneously essential – were often used by the great interior designers of Art Deco, from Jean-Michel Frank to Jacques Emile Ruhlmann and Robert Mallet-Stevens.

Owens has said that he especially appreciates long and narrow forms with small shoulders and high sleeves that fall producing creases and asymmetrical drapes, which are then contradicted by models suddenly revealing sculptural forms and volumes that invade the space, playing with it. “I try to make clothes the way Lou Reed does music, with minimal chord changes,” he explained. “It’s about giving everything I make a worn, softened feel. It’s about an elegance being tinged with the barbaric, the luxury of not caring” (The prince of dark design, 2011).

Harmonic ‘antinomies’ remain at the base of his poetics, which strive to bring together the opposites – the Apollonian and the Dionysian, the sacred and the profane, the individual and the tribe, romance and brutality, luxury and poverty, discipline and transgression – pledging to create an aesthetic based on the fascination of “disciplined excesses,” as he himself has defined.

When asked about his predilection for black, Owens often responds by addressing the role it has played in human social and material history, especially as an anti-status symbol of particular uniforms. Judges, monks, nuns and government agents have often separated themselves using a defined, monochrome silhouette, which since ancient times has signaled their disposal to serve others, conveying a significant renunciation of the self.

This concept applies to another recurring form of his unisex garments: the hood. The designer is fascinated by this unchanged, age-old shape and clear ergonomic development, magically summarized in its enduring simplicity and the incredible transversality of use, which according to Owens spans from Jesus Christ to Snoop Dogg, Dante Alighieri, Marlene Dietrich and Grace Jones.

His collections, as clearly exemplified in the Triennale, follow an invisible thread that connects the new to the archetype – the prototype to its serial reproductions – without ever losing narrative power.

Along with tailored forms and unusual textures, the Triennale offered a rather poetic and revealing take on the designer’s personality as witnessed in a black and white film – a slow, analytical work punctuated by the rhythm of the craftsman’s movements in his Concordia workshop. It was deliberately placed in a corner of the exhibit, as if only for those who wished to see the less obvious and theatrical details, but crucial for a deep understanding of Owens’ creative process.

The rituality of the movements, his endless precision in finding geometric balance in his cuts, combined with a passion for draping, tie Owens’ modus operandi to old school artists, who in their rough markings and creased fabrics have built unforgettable, poetic sartorial languages.

The infinite reproducing of folds and their incessant stratification orient Owens’ design process towards visual compositions – arithmetic relationships and “agreements” that contribute to the creation of the “new harmony” from which philosophy and art, as suggested by Gilles Deleuze, must not fail to gain inspiration: “[The Baroque] endlessly creates folds. It does not invent the thing: there are all the folds that come from the Orient – Greek, Roman, Romanesque, Gothic, classical folds…. But it twists and turns the folds, takes them to infinity, fold upon fold, fold after fold. The characteristic of the Baroque is the fold that goes on to infinity” (Le Pli: Leibniz et le Baroque, 1988).

And in Owens’ pleats and draperies, these historical understandings of the nature of the fold seem to coexist and stratify. His critical reinterpretation passes through the harmonious elegance of the delphos and peplos of Mariano Fortuny (a Spaniard living in Venice in the early nineteenth century, where Owens desired to buy a home), before reaching the complex ripples of Madame Grès, expertly manipulated for the purpose of weaving and knotting together light layers of white silk to create a sculptural aesthetic similar to Greek statuary. And finally, it penetrates the obsessive mathematics of Madeleine Vionnet’s crêpe and plissé soleil, who used the great Anglo-Florentine artist Thayaht to apply Pythagorean and Euclidean mathematics in pattern form. “I like classicism,” he continues in his 2011 interview with The Independent. “I like historic reference. I like something new with something almost ancient. I like [legendary costume designer] Adrian; Hollywood in the Twenties and Thirties.”

Moreover, the folds are revealed as an analogy, playing the role of cavities that never repeat themselves. It is thus a sign that produces signs, as each fold is an index that doubles and, in its indefinite ability to vary, contracts like a scar. And like scars, every fold seems intent on recounting its own story.

Owens was so fascinated by Thayaht, the multifaceted tightrope walker of Arts and Crafts, that he became an enthusiastic collector, taking inspiration from him both for his projects of functional and rationalist suits, as well as in his drawings that summarize and allude to Thayaht’s bronze, plaster, terracotta or steel heads, exhibiting a clear brutalist style.

As a tribute to the Florentine Futurist artist, Rick Owens even created a collection of jackets and scarves with the monochrome print of an ironic portrait of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti titled “Altoparlante Italico,” performed in 1935, of which the original sculpture is now in fashion designer’s Venetian home.

To this end, to underline the complexity of his aesthetic vocabulary – marked by esoteric implications binding him to the likes of Le Corbusier and Thayaht – the exhibit also displayed look-books, photographs, notes, pencil sketches, accessories in bronze, horsehair or bone, together with other objets particuliers, which little by little revealed myriad details and varied aspects of Owens’ mystical personality.

And among the pieces uncovering his most intimate hermetic and cabalistic vision, two are considered by Owens most symbolic of the balance of grace and power: a small straw nest and skull, always present on the designer’s work tables in both Italy and Paris, which inevitably accompany him in his frequent travels. The objects are explicit references to the mysteries of birth and death, containing enigmatic references to the hidden symbols of the letters “Α” (alpha) and “Ω” (omega), the beginning and end of the human parable – and the perfect symbols encompassing the totality of Owens’ work.

Credits

Written by:

- Aurora Fiorentini

- Federica Fioravanti